![]()

You might recall the debut of How Did You Do That?, a series focused on how makers create the things that we love. Nancy Liang kicked it off by sharing her GIF-making process. Now, I’m pleased to present something totally different — the making of an app! Brooklyn-based company Tinybop just finished their newest creation called The Robot Factory. It’s an opened-ended building app that lets kids make, test, and collect robots. How fun!

As with any app, there’s a lot of moving parts. I spoke with three people involved in making The Robot Factory happen (although there were many others): Tinybop CEO Raul Gutierrez came up with the concept; Owen Davey illustrated the app; and Leah Feuer was the project manager. They all have tasks that were integral to making the app happen, and they’ll help give us some sense of how The Robot Factory was created.

Coming up with the concept: Raul Gutierrez

Brown Paper Bag: What did you do before you founded Tinybop?

Raul Gutierrez: I was working in Hollywood on film and later in the startup world on the web, but always at the intersection of art and tech.

BPB: After you had the initial idea for The Robot Factory, what was the first step towards making the project a reality?

RG: Probably the original inspiration for the app was an Apple ][ game called Pinball Construction Set. I remember thinking back then, “Building pinball machines is cool, but it would be so much cooler to build robots.” I was part of the first Star Wars generation. All the kids back then thought that when we reached the 2000’s the world would be full of robots. Maybe this app is my small attempt to make that imagined future a little more real.

The first step in actually starting the project was building a company and surrounding myself with lots of smart creative people.

RG (answer continued): We kicked off this app at the end of 2014, it wasn’t the first app we tackled because we wanted to have the right team in place.

We choose the artist [Owen Davey] for this project because we knew he loved robots too and we loved his art. To kick off we created a mood board full of robots to inspire him (50’s and 60’s Japanese robots were a big influence). Our engineers are all obsessed with physics based animations, so they dug into the project. By physics-based animations we mean that when robots move, it’s not just a precanned set of frames, we actually connect objects and define their physics so they move together in realistic ways. We even attach sounds to joints so that things creak and whir correctly as the bots speed up or slow down.

BPB: This app has so many unique and seemingly-endless possibilities for building robots and having fun with them. How did you come up with it all? What type of research was required, and did that inform or change any of your beginning concepts?

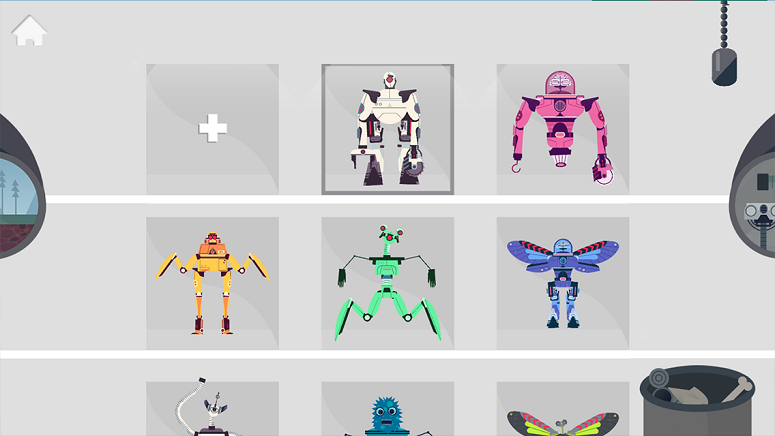

RG: We started with contained idea. “Let kids build robots with few restrictions and bring them to life. They’ll enter a world and want to run. Robots just want to run. The bots will work or fall apart depending on their physics.” We didn’t want to define things too much so that kids could fill spaces with their imaginations.

Everything else came out of that. Our artist had to create a system of interlocking parts and a world to run in. Our engineers had to figure out how to make the parts move realistically and fit together as a whole, and later to run and jump and fly… Our sound designer designed an entire tiny universe of sounds for this little robot world we created.

RG (answer continued): The hope is that kids don’t notice any of the tech. They just want their robots to come alive. Hearing kids’ stories after they playing with the app is super satisfying. They give their robots names. They invent backstories. They make connections that have little to do with what’s on screen. But we’ve given them the right tools to give form to their imaginations.

This is just the beginning for this title, the MVP or Minimum Viable Product to use the term of art. We have so much more we want to add and already have a ton of cool new parts on deck. I can’t wait to get them out there.

BPB: What tools/programs/websites etc. do you find helpful when working/creating The Robot Factory?

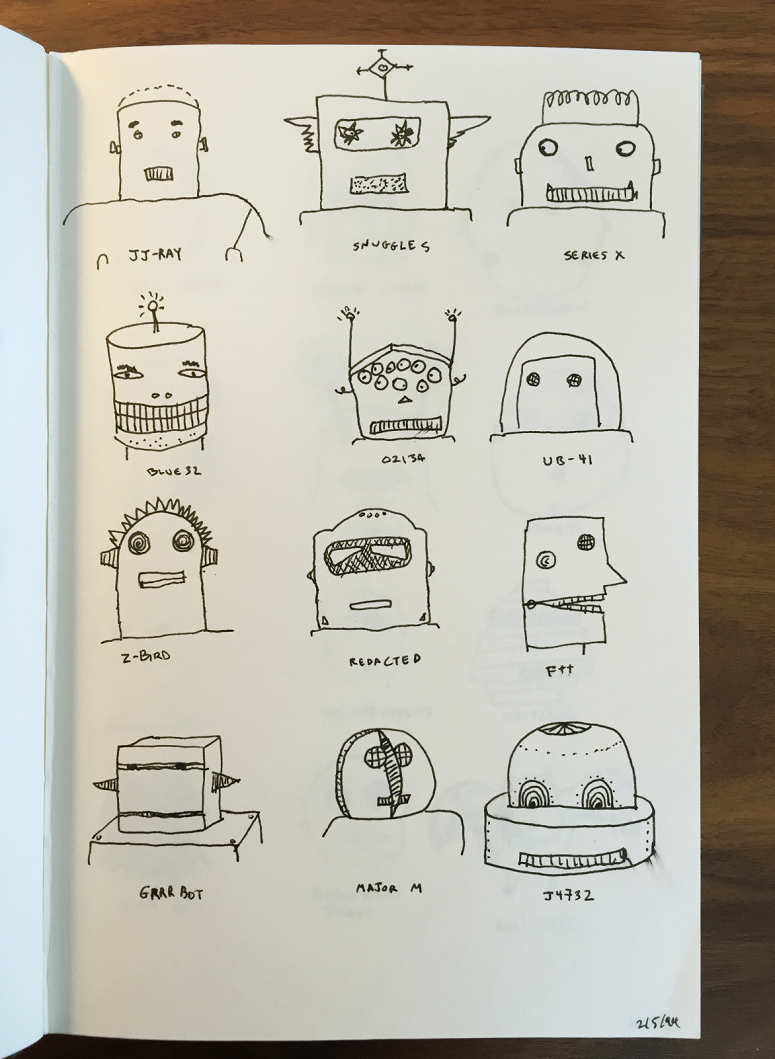

RG: I always start with pen and paper and try to pull together inspiration from wherever I can find it.

Creating the illustrations: Owen Davey

BPB: What did you use as inspiration for your robot characters?

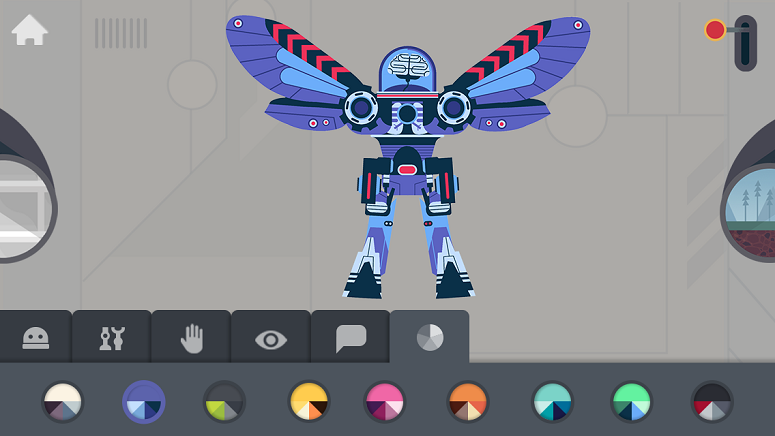

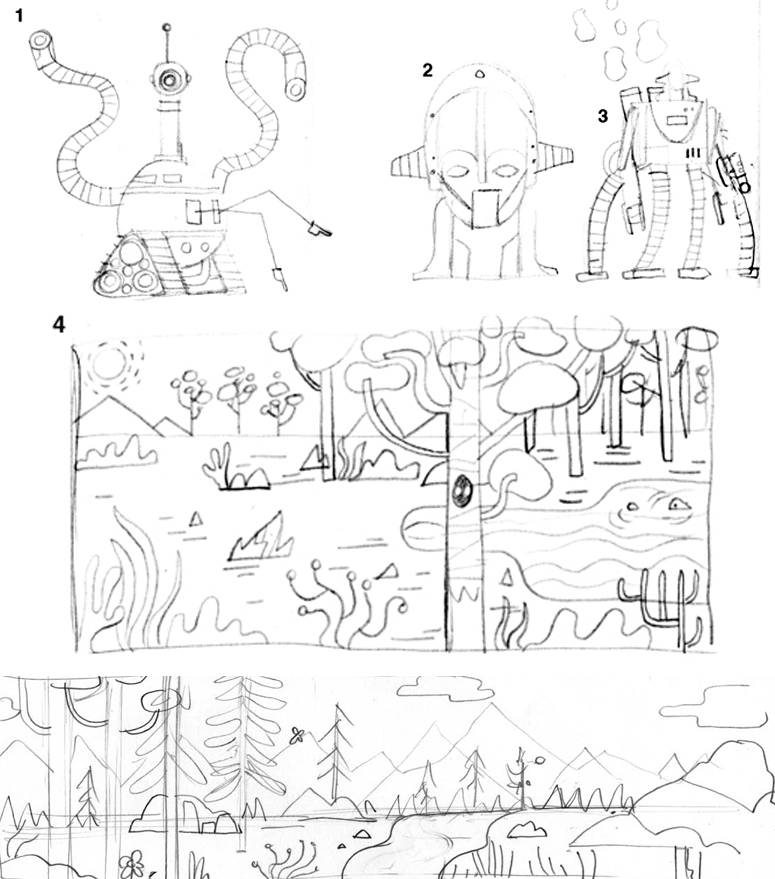

Owen Davey: It was essentially a mix of all the real robots that have actually been built in the real world (some fact is stranger than fiction, believe me), inspiration from loads of sci fi films/ tv and computer games, and then my own imagination created by my inner child. The robots weren’t designed as whole individuals, but rather individual pieces that could create the maximum number of different styles of robots. If kids (or adults want), they can attempt to recreate something reminiscent of their favorite famous robot, or can instead just run wild with their own ideas and see where it takes them.

BPB: How did you create your illustrations for use in an app?

OD: I tend to work in Photoshop. Many people cringe at this and think I should be using Illustrator, but I’ve been using Photoshop for over 10 years and it’s second nature to me. I can work in Illustrator, but I tend to freeze up a little bit and I’m never as happy with the result. I usually start my illustrations with sketches, scan them and then use them as a guide. It helps keep the process more organic for me, and helps keep some of my artistic sensibilities, rather than homogenizing my work.

BPB: What was different about producing illustrations for an app? Did it change the way you normally work?

OD: Oh my word. It is really tough! Everything you create has a knock-on effect. You draw an arm that looks cool and if you’re doing one image then great, you’re done. In an app, you then have to draw it from the side. suggest how it might work from in front or from the side, come up with some color suggestions for it etc etc. One of the toughest things was trying to work out how the pieces would fit together too, because you construct from the front, but use your robot from the side. So if you put a head on a body in the creation bit, does it sit centrally / to the side / on the back etc. in the world? It was very different to my usual work process but nice to hurtle myself out of my comfort zone.

BPB: What did you learn from illustrating The Robot Factory?

OD: I don’t often do such labor-intensive collaboration with most of my work, so it was a good one for that. Everything I illustrated influenced other people who then did stuff to it, then it came back around to me and I needed to edit, enhance or add to what I’d already done and then the whole process would happen again. I usually have a few amends to make with each illustration I do, but this was a continually evolving beast that needed assessing and reassessing. That is definitely a new skill I have learnt to embrace.

Bringing it all together: Leah Feuer

BPB: What is your role as a project manager? How many people did you work with to see The Robot Factory to completion?

Leah Feuer: As a product manager at Tinybop I am a map maker, a funnel, an interpreter and a herder of cats/mother of dragons. I worked with 20+ people to get the app into the wild. The core app team was ~10.

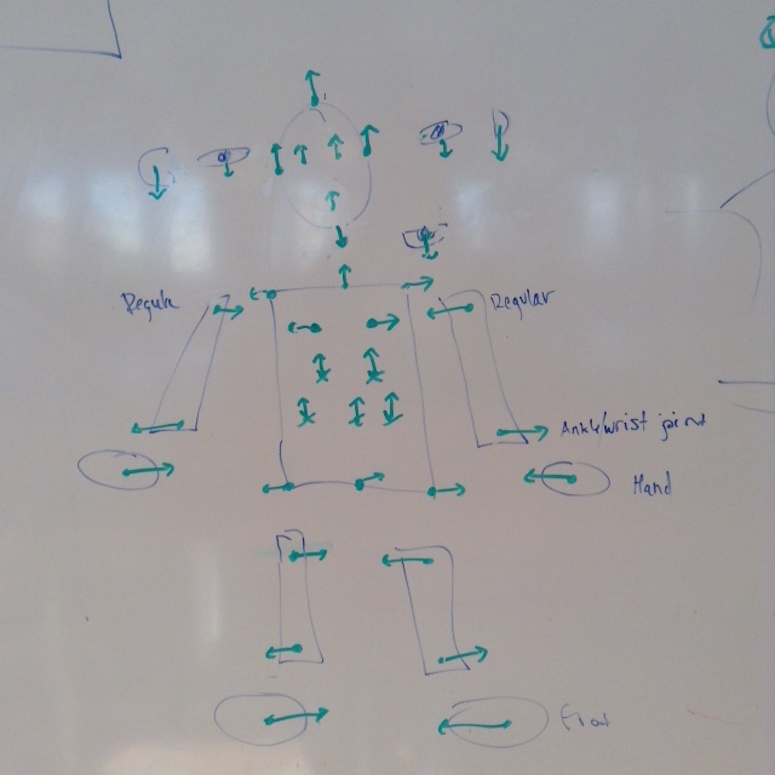

As map maker, I draw out everything from the next features that need to be implemented in The Robot Factory to our long term product roadmap. Sometimes I’m charting unknown territory: exploring what different concepts might look like as apps and how they fit into the Tinybop universe.

As a funnel, I’m listening to ideas from the team and beyond and figuring out which ones make sense for us to explore further. It’s really important to have both a bucket full of ideas, and a paired down achieve-able set that the team can focus on tackling. I interpret ideas into features and things that can be implemented by the team. I also do a bit of language interpreting. Sometimes developers speak a different language from designers, kids a different language from investors, etc. Keeping the lines of communication open and clear is an important part of the role.

BPB: How did your team take Owen’s (non-animated) illustrations and turn them into something that’s engaging and interactive?

LF: This was a super cool part of the process. We knew we wanted each robot part to come alive in different ways and affect how the robot moves in the world. To do that we had to:

Remake Owen’s art in Unity out of a limited number of basic shapes to save space and improve app performance. Almost all Robot parts were made by combining pills and circles and like these:

LF (answer continued): Design a flexible, smart system for connecting robot parts, so you can make the robot of your dreams. We ended up using “connection points” (similar to joints and sockets) on each part. We carefully placed the points on each part and added a few rules about how they connect to prevent super wonky things from happening.

LF (answer continued): Animate the parts, so they come alive in the factory

[KGVID width=“775” height=“436”]https://www.brwnpaperbag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/speed.mov[/KGVID]

[KGVID width=“775” height=“436”]https://www.brwnpaperbag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/circularhead.mov[/KGVID]

[KGVID width=“775” height=“436”]https://www.brwnpaperbag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/EyeDisguise_Anim.mov[/KGVID]

LF (answer continued): Use physics to make the robots move in the world and respond to different obstacles. This was a huge challenge, but when we started to get robots that could actually walk, fly and fist bump, it was really amazing.

[KGVID width=“775” height=“436”]https://www.brwnpaperbag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/4bananapeels.mov[/KGVID][KGVID width=“775” height=“436”]https://www.brwnpaperbag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/learningtoflysm.mov[/KGVID]

LF (answer continued): Add sounds for each part and the various ways and speeds at which it moves.

Give the robot emotions and a voice. Each robot makes sounds based on its mood (happy, sound, bored, hurt, etc.). We designed some of our own sounds and let kids add their own too!

A lot of things did not go according to plan during this process — parts not staying together, robots jittering or floating instead of walking, etc. They really did seem to have a life of their own at the end of all this.

[KGVID width=“775” height=“436”]https://www.brwnpaperbag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/youdroppedsomething.mov[/KGVID][KGVID width=“775” height=“436”]https://www.brwnpaperbag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/blooper-cut-sm.mov[/KGVID]

[KGVID width=“775” height=“436”]https://www.brwnpaperbag.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/derpod.mov[/KGVID]

BPB: What kinds of tools/programs were used to bring The Robot Factory to life?

LH: So many! Here are some that come to mind:

Paper, pencils, markers, coffee, google docs, scissors, whiteboards, robot magnets, HipChat, pivotal tracker, rice crispy treats, proto.io, the internet, Photoshop, Dropbox, servo motors, microphones, pro tools, clicks, beeps, a Roland Juno 60, Unity and a bunch of custom tools we made for Unity.

Thanks, ya’ll! Now everyone — check out this beautiful app and download it from the iTunes store.